|

Few Westerners are aware that, for thousands of years, China was far

more developed than the West. In this article we

will examine the Confucian

culture, that created the basis for the Chinese to make a series of remarkable

inventions,

and how these inventions allowed China to achieve a

much higher living standard, than existed anywhere else at the time

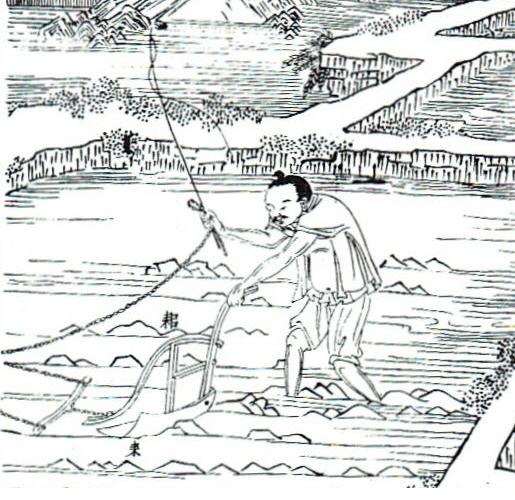

A Chinese Seed Drill: This technology was used in China for

thousands of years before it was introduced into Europe

China is one of the few nations in the world that is currently carrying

out great infrastructure projects similar to

those that were essential

to the development of the United States. This is exemplified by the

Three Gorges Dam, plans

to build railroads to develop the western

regions, and China's collaboration with the nations of Asia and Europe

in

the development of the Eurasian Land-Bridge. The forward-looking

nature of China's policies is exemplified by the fact

that China is the

first nation to begin construction of a magnetically levitated train,

while projects to build magnetically

levitated trains have been canceled

in the West.

Few Westerners realize today, that for much of Ancient times,

and the

Middle Ages, China was significantly more advanced than Europe. In this

article, we will examine a number

of the technological breakthroughs made

in ancient China, and the Confucian outlook that encouraged these

discoveries.

We will also examine this period of Chinese history, from

the standpoint of the principles of economic science that were

developed

by Lyndon LaRouche, to see the relationship of these technological

breakthroughs to the development of

China's economy.

Foolish people today (including, unfortunately, many in Congress and the

present Administration),

seem to think that China's identity is defined

by the last half-century, i.e., that it was always Communist. However,

that period of Chinese history, from which it has been re-emerging in

recent years, represents only {one percent}

of its 5,000-year history!

The paradox thus posed is: How has this civilization survived and

prospered for five millennia,

to become the most populous nation on Earth?

China's Confucian Tradition

``Now when food meant for human beings is so plentiful as to be thrown

to dogs and pigs, you fail to realize that it is

time for garnering,

and when men drop dead from starvation by the wayside, you fail to realize

that it is time for

distribution. When people die, you simply say, `It is

none of my doing. It is the fault of the Harvest.' In what way is

that

different from killing a man by running him through, while saying all the

time, `It is none of my doing. It

is the fault of the weapon.' Stop

putting the blame on the harvest and the people of the whole Empire

will come

to you'' (Mencius, Book 1 Part A, 3).

The successes of ancient China in economic development were the result of

the influence of the Confucian philosophical school, led by Confucius

(551-476 B.C.) himself, and his follower, Mencius

(372-289 B.C.). Both

recognized an absolute distinction between mankind and the beasts,

asserting that man's nature

was essentially good, and capable of being

governed by reason.

Confucius taught that society must be governed,

not by selfishness and

greed, but by the Chinese concept, ren, which is very similar to the

Platonic and Christian

concept of agapee (a Greek word, usually translated

as ``love,'' or ``charity''). Confucius proclaimed what the West

would later

call the Golden Rule: ``Is there one word which may serve as a rule of

practice for all one's life?''

The Master said, ``Is not `reciprocity'

such a word? What you do not want done to yourself, do not do to others.''

Moreover, some 2,200 years before the Preamble to U.S. Constitution was

adopted, Confucius and Mencius established

the responsibility of

government to promote the General Welfare. Although society was still

hierarchically ordered,

with the Emperor exerting absolute rule over his

subjects, he was required to ensure their livelihood, or risk losing

the

mandate of Heaven. As Mencius stated, ``Heaven sees with the eyes of its

people. Heaven hears with the ears

of its people''; he quoted from the

``Book of History,'' to indicate that societies are destroyed, not

by natural

disasters, but by human folly:

``When Heaven sends down calamities,

There is hope of weathering them;

When

man brings them upon himself,

There is no hope of escape.''

However, Confucianism was often opposed by antithetical

ideologies, such

as Daoism, which had a very destructive effect when they were dominant.

When governments strayed

from Confucian principles, the result was

often civil war and massive depopulation.

In the classical work of

Daoism, the 'Dao Te Ching,' the Lao Zi, (Sixth

Century) taught that the king rules by keeping his people ignorant: ``He

empties their minds, and fills their bellies;|... He strives always to keep

the people innocent of knowledge and

desires, and to keep the knowing ones

from meddling.'' Daoism rejected the Confucian concept of government's

responsibility

to promote the General Welfare, arguing that events should

simply take their course.

The European Renaissance

and the foundation of the nation-state in the

15th Century, in Louis XI's France and Henry VII's England represented

a

fundamental advance for all mankind, that allowed human society to achieve

rates of growth that were unprecedented

in human history. However, during

much of the period prior to the Renaissance, the Chinese economy achieved

a level

of productivity, that far exceeded that of Europe. Central to this

development, was the Confucian conception of man as

governed by reason, and

not bestial emotions, which guided the Chinese to make a remarkable series of

discoveries,

many of which were not made in Europe, until much later.

Government That Promotes the General Welfare

Chinese governments carried out numerous initiatives to develop agriculture,

which was by far the largest sector of the

economy at that time. The ``Lu shi

chun qiu,'' or ``Master Lu's Spring and Autumn Annals,'' written around

250-225

B.C. states:

``The ruler shall order the work of the fields to begin. He shall order the

inspectors of the fields

to reside in the lands having an eastern exposure,

to repair the borders and boundaries of the fields, to inspect the

paths and

irrigation ditches, to examine closely the mounts and hills, the slopes and

heights and the plains and valleys

to determine what lands are good and where

the five grains should be sown, and they shall instruct and direct the people.

This they must do in person. When the work of the fields had been well begun,

with the irrigation ditches traced out

correctly before-hand, there will be

no confusion later.''

Governments actively promoted the development of

new technologies in

agriculture, and often took initiatives to insure their use by the peasants.

This is evidenced

by the fact that over 500 tracts were produced, many of them

by government officials, dating back over 2000 years, developing

the science

of agriculture. These tracts covered a wide range of crops, and the entire

range of techniques and technologies

necessary to develop productivity, such

as plowing, sowing, irrigation and cultivation.

Chinese writings on

agriculture were vastly superior to those produced in

Europe, until as late the 18th Century. Roman works on farming remained

the

main writings used throughout the Middle Ages. These Roman tracts dealt with

the management of slave estates to

produce wine and olive oil, with little on

other crops. Only the Arabs introduced new techniques into Europe, before the

Renaissance.

Confucianism--like its distant offspring, the American System of National

Economy--rejected

``free trade,'' and promoted government intervention to

insure the General Welfare. The "Han shu shi huo zhi' (``Han

Book on Food and

Money''), the first economic history of China, published in the First Century

A.D., discussed actions

of the government to control speculators, who enriched

themselves, through actions that impoverished or starved the people.

For

example, the Han dynasty practiced a policy akin to parity-pricing for

agriculture, with its ``ever-level price

granaries.'' The government purchased

grain during times of surplus, and sold it during times of shortage, in order

to

maintain a stable price. The price of many commodities was regulated to

reflect the cost of production.

Free

trade or ``laissez-faire'' economics, popularized by British East India

Company agent Adam Smith, and adopted by the 18th-Century

French Physiocrats,

was based on a ``hedonistic principle,'' which Confucianism rejected.

Francalois Quesnay, one

of the creators of the Physiocratic doctrine, stated,

``To secure the greatest amount of pleasure with the least possible

outlay

should be the aim of all economic effort.'' The Physiocrats would later falsely

claim that the success of the

Chinese economy, was proof of their ideology,

which asserted that only agriculture was truly productive.

However,

to understand agriculture, or any sector of an economy, it is necessary

to examine the processes that determine the economy

as a whole. Contrary to the

assertions of the French Physiocrats, the success of Chinese agriculture was

based on

technological breakthroughs, that gave the Chinese a superior

tool-making industry. Indeed, this is illustrated by the

'Han shu,' which states,

``Iron may be called a fundamental in farming.

The Science of Economics

The science of economics was founded by Leibniz and further developed by Lyndon LaRouche. We will discuss some of the basic

concepts expressed in LaRouche's text, "So You Wish to Learn About Economics."

Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716),

who founded the science of Economics, studied the application of heat powered machinery to increase the power of the worker.

As LaRouche states, "The increase of man's power over nature is most easily measured as a decrease of the habitable land

area required to sustain an average person." A more accurate measurement is not simply the existing population density,

but the potential level of population that a given technology can support, the "potential relative population-density."

No economy can remain in a fixed level of technology. If a society does not advance to a higher level of technology,

it will run into limits, as it exhausts the resources that are available, at that level of technology. As LaRouche states,

"Only societies whose cultures commit them to successful technological progress, as a policy of practice, are qualified

to survive and to prosper."

Technological breakthroughs can occur on two levels: 1) those that increase the

productivity of labor, for example, the introduction of a more efficient plow. 2) a technological revolution that moves society

to a completely higher level of technology, for example, the introduction of electricity. The measure of economic value and

work is the rate of increase of potential relative population-density, relative to it's existing level.

A successful

economy must meet a number of conditions. The living standard of the population must rise. However, even as the living standards

of the population rise, investment in capital goods must rise even more rapidly, causing the capital intensity of the economy,

to increase. A successful economy must increase the surplus that it invests in the development of new technology even more

rapidly. It must also make necessary investments in basic infrastructure such as transportation, water supplies, and health

care and education.

We will now examine the development of the Chinese economy over the last 2500 years, keeping

these principles in mind. We will see how China's technological breakthroughs led to increases in the potential relative population-density.

Chinese Metallurgy: The Basis For Superior Tools

A Chinese Blast Furnace

The Iron Age is generally considered to have begun around

1700-1500 B.C. The introduction of iron allowed mankind to

develop tools that were stronger and superior to stone or bronze. These improved tools increased productivity.

The

manufacture of iron requires two processes: First, the iron, which naturally occurs in the form of an ore of iron oxide, must

be separated from the oxygen and other impurities, in a high-temperature process, which is

called reducing or smelting.

The oxygen is removed by combining it with carbon, to form carbon dioxide. This leaves behind the iron in metallic form. The

other impurities form a slag, which is then separated. Second, the raw iron must be manufactured into useful articles.

The earliest smelting of iron ore was done at temperatures below the melting point of iron, which is higher than that

of copper and bronze. Iron, produced by this method, forms a spongy solid, when it is removed from the furnace. Furnaces that

reduced iron ore to its metallic form, while operating below the melting point of iron, were called bloom furnaces.

Once the reduction of iron ore to its metallic form has been accomplished, it must be shaped into a useful article. Transforming

the spongy raw iron into a useful article, was a slow, and very inefficient process, which only allowed the production of

simple shaped utensils, such as swords.

However, by no later than the end of the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476

B.C.), the Chinese developed the technology of the blast furnace. This allowed them to heat the ore above its melting point,

and produce cast iron. Among the inventions that made this possible, was the double-action bellows. The manufacture of iron,

using a blast furnace to produce a molten metal, greatly expanded production: The process could be continuous, as the molten

metal flowed from the reducing furnace, was poured into molds, and made into a large variety of products.

Casting a bell

The blast furnace was introduced in Europe, on a wide scale, only in the late 14th Century, almost 2,000 years later. The

use of cast iron was, unfortunately, introduced in Europe largely for the production of cannon; Henry VII constructed the

first blast furnaces in England. The replacement of the bloom furnace with the blast furnace, increased productivity in the

English iron industry 15-fold.

The Chinese were able to manufacture superior tools, that the more primitive European

metallurgy was incapable of producing, which led to a substantial advance in productivity throughout the entire economy. As

early as the Third Century B.C., the state of Qin appointed government officials to supervise the iron industry, and penalize

manufacturers who produced substandard products. The Han Dynasty nationalized all cast-iron manufacture in 119 B.C. Around

that time, there were 46 imperial Iron Casting Bureaus throughout the country, with government officials insuring that cast-iron

tools were widely available. This included cast-iron plowshares, iron hoes, iron knives, axes, chisels, saws and awls, cast-iron

pots, and even toys.

The Chinese also developed methods for the manufacture of steel that were only matched in the

West, in the recent period. The characteristics of iron alloys are related to the carbon content. Cast iron generally has

a high carbon content, which makes it strong, but brittle. Steel, which is an alloy of iron with a low carbon content, is

strong and more durable. The use of steel in agricultural implements was introduced, on a wide scale, during the Tang Dynasty

(618-907 A.D.). This led to a further improvement in productivity.

In the Second Century B.C., the Chinese developed

what became known in the West as the Bessemer process. They developed a method for converting cast iron into steel, by blowing

air on the molten metal, which reduced the carbon content. In 1845, William Kelly brought four Chinese steel experts to Kentucky,

and learned this method from them, for which he received an American patent. However, he went bankrupt, and his claims were

made over to the German, Bessemer, who had also developed a similar process.

As early as the Fourth Century A.D.,

coal was used in China, in place of charcoal, as fuel to heat iron to rework the raw iron into finished products. Although

sources on the use of coal in the Song Dynasty (960-1279 A.D.) are limited, the Chinese are reported to have developed the

ability to use coal in the smelting of iron by the Ninth Century.

The use of wood to make charcoal was causing deforestation,

which threatened to limit the production of iron. Indeed, the development of the capability to use coal in iron manufacture

is an example of how a new technology allows mankind to overcome limits imposed by existing levels of technology. The rapid

expansion of iron production that occurred under the Song Dynasty, would not have been possible without the introduction of

coal as an energy source in the production of iron.

Under the Song dynasty, the iron and steel industry reached

a level that was spectacular, compared to that in Europe. Between 850 and 1050, iron production increased 12-fold. By 1078,

North China was producing more than 114,000 tons of pig iron a year. In 1788, seven hundred years later, England's production

of pig iron was around 50,000 tons.

Chinese Agricultural Productivity: The Result of Superior Technology

Breugel's painting shows a man plowing with an inefficient European plow

``Master Lu's Spring and Autumn Annals'' describes how each spring, the Emperor and his chief ministers initiated the growing

season, with a ceremony in which each took turns plowing the ground. The plows they used were dramatically superior to the

plows that were used in Europe, until the 18th Century. Writer Robert Temple has observed that, ``Nothing underlines the backwardness

of the West more than the fact that for thousands of years, millions of human beings plowed the earth in a manner which was

so inefficient, so wasteful of effort, and so utterly exhausting, that this deficiency of sensible plowing may rank as mankind's

single greatest waste of time and energy.''

Plows prepare the ground for planting, by using an iron share to cut

into the ground, and a mould-board to turn it, burying the weeds and loosening the soil. In 1784, the Scottish agricultural

scientist, James Small, enunciated the following principles of scientific plow design:

``The back of the sock [share]

and mould-board shall make one continued fair surface without any interruption or sudden change.'' Chinese plows, from the

Third Century B.C., already met these requirements. They had a cast-iron mould-board, which was a curved device, that shifted

the soil with the minimum of drag. The European plow simply had a wooden board coming off to the side which turned the soil,

that had been cut.

A Chinese cast iron plow

In 'So You Wish to Learn All About Economics?,' Lyndon LaRouche developed the basic principles of technology. In it, he states,

``Generally speaking, the power applied to the work by a machine is not the same power supplied to the machine as a whole.

A very simple machine, a simple knife blade, illustrates the point: the pressure applied by the sharpened edge of the blade

is vastly greater than the pressure exerted upon the handle of the knife. The power is more concentrated. We measure such

concentration of power as increase of energy-flux density.''

The Chinese plow concentrated the force much more efficiently

on the sharp blade of the plow, with the mould-board designed to turn the soil with a minimum of drag. With the European plow,

the entire straight wooden mould-board pushed against the soil. Therefore, the Chinese plow achieved a far higher energy-flux

density, and accomplished far more work with far less effort. Chinese plows were so efficient, that they required only one

or two animals to pull them. Four, six, or even eight draft animals were needed to pull the inefficient European plow. The

Chinese plow was vastly more efficient than the European plow, both per worker and per unit of energy used. As LaRouche states,

``This difference is Leibniz's definition of the subject matter of technology.''

Row Agriculture and Weeding

Paul de Limbourg and Colombe, October, Tres Riches Heures, Musee Conde, Chantilly

The method used in Europe to plant seeds, as late as the 18th Century, was extremely wasteful and inefficient. A painting

by the Limbourg Brothers for the Duc de Berry (ca. 1415) 'Les Tres Riches Heures,' to illustrate the month of October, demonstrates

the inefficency of the methods for planting that were used in Europe until the 18th Century. In the lower righthand corner,

a peasant tosses seeds, from a sack he carries, onto the ground. Behind him, another peasant is riding a horse that is pulling

a rake. The purpose of the rake was to cover the seeds with soil; a very unreliable method, that left many seeds exposed.

Appropriately, pictured in the lower left, is a flock of birds, who are busily eating the seeds.

This method was

so inefficient that most of the seeds never germinated to produce a crop. The plants also grew up in a disorganized mess.

Weeding the fields was impossible, so the plants were left to compete with the weeds until harvesting season. This considerably

reduced the crop. In Europe, it was often necessary to save one-half of the harvest to use as seeds the next year.

By

no later than the Sixth Century B.C., the Chinese adopted the practice of growing crops in evenly spaced rows, and using a

hoe to remove the weeds. ``Master Lu's Spring and Autumn Annals,'' states ``If the crops are grown in rows they will mature

rapidly because they will not interfere with each other's growth.

The Seed Drill

At first, the seeds were placed by hand in furrows, in a ridge-and-furrow pattern. Around the Second Century B.C., the Chinese

introduced the seed drill, which became almost universally used in northern China. This device consisted of small plows that

cut small furroughs in the ground, a mechanism that released the seeds, evenly spaced into these furrows, and a brush or roller

that covered the seeds with dirt. The seed drill could be adjusted for different types of soil and seeds. This method of planting

was so much more efficient than sowing the seed by scattering it, that it could achieve an efficiency 10 or even 30 times

greater.

It should be easy to see that the difference in productivity between Chinese and European agriculture was

dramatic. The area of land that could be brought under cultivation in Europe was constricted by inferior technology, and by

the need to leave more land as pasture to feed the extra draft animals. Obviously, we are comparing two large areas, over

a long period of time. However, Chinese yields have been estimated at two, five, or even ten times higher than yields in Europe,

at various times. China's higher yields allowed for an increased population density, and also for an increased division of

labor, as we will see below.

Eventually these technologies were transmitted to Europe, which led to a large increase

in agricultural production. European travelers were greatly impressed with the wealth of China, and the productivity of its

agriculture. Leibniz and others actively sought out information on Chinese science, industry and agriculture from Europeans

who traveled to China.

The Chinese plow and seed drill were introduced into Europe during the 17th Century, and

gradually adopted throughout Europe. Growing crops in rows was championed by British agricultural reformer, Jethro Tull, who

printed a treatise in 1731, to persuade farmers to adopt what he called ``horse-hoeing husbandry.'' Tull published arguments

similar to those used 2000 years earlier in China. Tull also developed one of the first successful European seed drills.

Transportation and infrastructure

Confucian philosophy placed the responsibility for the development of infrastructure on the ruler. The development of inland

water transport, which is far less costly than overland transport for bulk commodities, was essential for the growth of a

large-scale iron industry, and for transporting the large quantities of grain needed by China's cities. Even into modern times,

the length of China's transportation canals has exceeded those of Europe.

In 1615, the missionary-scholar Matteo

Ricci, who lived and taught in China for many years, reported, ``This country is so thoroughly covered by an intersecting

network of rivers and canals that it is possible to travel almost anywhere by water.'' He also estimated that there were as

many boats in China as in all of the rest of the world. From 1405 to 1433, Chinese fleets under Admiral Zheng He carried out

seven expeditions reaching as far as Africa and the Red Sea. The first fleet consisted of 317 ships and 26,800

men.

Around 215 B.C., the first contour canal was built in China, which linked the Changjiang (Yangtzee) and the Zhujiang

(Pearl) river systems. The Grand Canal is the longest and largest of all navigation canals in the world. Completed during

the reign of Emperor Yang Di (604-17 A.D.), it extended 1,250 miles from the Changjiang River to Beijing. During the Tang

Dynasty, over 2 million tons of grain were shipped, yearly, north on the canal. This increased to 7 million tons during the

Song Dynasty.

Numerous water projects were developed for irrigation, from as early as 600 B.C. Major dike projects

were also built to control rivers, and protect the coastline.

Roads and Horse Harnesses

The Chinese also developed an extensive network of roads. By 210 B.C., 4,000 miles of imperial highways, equal to the distance

built by the Romans, had been constructed in China. The Chinese made major innovations in bridge construction. A number of

bridges were so well designed, that they are still in use over 1,000 years later. One bridge, built in 610 A.D., that still

survives, bears the inscription to its designer, Li Ch'un: ``Such a master-work could never have been achieved, if this man

had not applied his genius to the building of a work which would last for centuries to come.''

Under the Roman Empire,

even the horses had an inferior existence to those living in China. The Romans used a throat-and-girth harness that went around

the horse's neck. This choked the poor horse with the least exertion. In the Third and Fourth Century B.C., the Chinese made

two improvements in horse harnesses, which placed the force of the load on the horse's chest bones, rather than its throat.

Studies have shown that the Chinese harnesses allowed a horse to pull a load six times greater that of a horse in a throat-and-girth

harness. These Chinese harnesses were brought to Europe through Central Asia, thereby liberating Europe's horses from choking

harnesses, and improving Europe's ability to transport goods. This same path was followed by the stirrup, another Chinese

invention which greatly improved man's ability to ride a horse, without falling offand for long distances with less exertion.

Ancient China's Remarkable Cities

It can be easily seen that superior Chinese technology made

possible a much higher productivity in agriculture, both

per-person and per-hectare. This allowed the Chinese economy to support a larger proportion of its population in non-agricultural

employment, and allowed the development of a level of urbanization that was unprecedented in Europe until after the 15th-Century

Renaissance.

Although the following figures are estimates, the strongest evidence of their accuracy is that the

Chinese had developed a level of technology capable of supporting such large urban centers.

The largest city of

the Warring States period (475-221 B.C.), Linzi the capital of the state of Chi, reached a population of approximately 300,000.

In 300 B.C., at least nine cities, containing more than 100,000 people can be identified. Approximately 4.3 million people,

or approximately 14%, lived in urban centers, (defined as 2,000 or more).

During the Second Century B.C., Xi'an

was the largest city in the world. Luoyang, the capital of the Eastern Han Dynasty, reached a population of 500,000 during

the First Century A.D. It had an imperial observatory, where Zhang Heng created his seismograph, and advanced his theory that

the Earth was spherical; an Academy, attended by 30,000 students; and a granary for times when food relief was needed.

Under the Song Dynasties (960-1279), China's cities reached their height of development. Lin-an, (Hangzhou) the capital

of the Southern Song reached 2.5 million by 1200. In addition, there were two other cities of 350,000 each, and others were

more than 100,000 each. By contrast, in 1200, the largest cities in Western Europe, were Florence and Venice with about 90,000

each, and Milan with 75,000. The largest European cities during the Middle Ages were Constantinople and Cordoba. Constantinople,

in today's Turkey, reached around 600,000 to 800,000 in 1100. Cordoba, in Muslim Spain, reached 400-500,000, but then declined.

The level of urbanization in China has been estimated at around 20% in 1200. France and England did not reach a 20% level

of urbanization until the 18th Century. It can be easily seen that superior Chinese technology made possible a much higher

productivity in agriculture, both per-person and per-hectare. This allowed the Chinese economy to support a larger proportion

of its population in non-agricultural employment, and allowed the development of a level of urbanization that was unprecedented

in Europe until after the 15th-Century Renaissance.

Although the following figures are estimates, the strongest

evidence of their accuracy is that the Chinese had developed a level of technology capable of supporting such large urban

centers.

The largest city of the Warring States period (475-221 B.C.), Linzi the capital of the state of Chi, reached

a population of approximately 300,000. In 300 B.C., at least nine cities, containing more than 100,000 people can be identified.

Approximately 4.3 million people, or approximately 14%, lived in urban centers, (defined as 2,000 or more).

During

the Second Century B.C., Xi'an was the largest city in the world. Luoyang, the capital of the Eastern Han Dynasty, reached

a population of 500,000 during the First Century A.D. It had an imperial observatory, where Zhang Heng created his seismograph,

and advanced his theory that the Earth was spherical; an Academy, attended by 30,000 students; and a granary for times when

food relief was needed.

Under the Song Dynasties (960-1279), China's cities reached their height of development.

Lin-an, (Hangzhou) the capital of the Southern Song reached 2.5 million by 1200. In addition, there were two other cities

of 350,000 each, and others were more than 100,000 each. By contrast, in 1200, the largest cities in Western Europe, were

Florence and Venice with about 90,000 each, and Milan with 75,000. The largest European cities during the Middle Ages were

Constantinople and Cordoba. Constantinople, in today's Turkey, reached around 600,000 to 800,000 in 1100. Cordoba, in Muslim

Spain, reached 400-500,000, but then declined. The level of urbanization in China has been estimated at around 20% in 1200.

France and England did not reach a 20% level of urbanization until the 18th Century.

Successful Economic Development

The development of a large urban population allowed the Chinese economy to achieve a higher division of labor, which was the

basis for further increases in productivity. Mencius described the importance of a large division of labor: "Moreover,

it is necessary for each man to use the products of all the hundred crafts. If everyone must make everything he uses, the

Empire will be led along the path of incessant toil." Mencius Book III Part A.4

China's cities were centers

for education and scientific research, an example of how a society should reinvest it's surplus product, into research to

discover new technologies that further increased the societies potential relative population-density. Furthermore, the higher

educational level created the conditions for China to develop a rich culture in art and poetry. This further increased the

societies potential to make scientific discoveries, since the principles of scientific discovery are the same as the principles

of metaphor in good art and poetry.

Although China went through a number of very troubled times, China's economic

development, in many of periods up through the Song dynasty, was remarkably successful for a nation, during this period in

history. China's development during successful periods can be compared to the conditions for development that we discussed

earlier.

* The living standard of the population) was increasing.

* The level of capital investment was increasing.

This can be seen in areas such as the growth of iron production, which far exceeded any other country on earth.

* A surplus

was produced that was invested in crucial areas such as education. For example, during the Song Dynasty, the state school

system was capable of supporting 200,000 students.

* Improvements in technology were allowing the Chinese economy to

produce this increased product with less effort.

* The Chinese were making significant scientific discoveries that further

improved the productivity of Chinese society. For example, the Chinese invented printing, and China under the Song Dynasty

was the first society with the widespread use of printed books, greatly increasing the transmission of ideas.

* All of

this is reflected in the increased potential relative population density, and the increased level of urbanization.

Scientific Discovery is Necessary for Survival

In the 13th Century, China was hit by catastrophe, with the Mongol invasion. The level of genocide is illustrated by the drop

in the population from approximately 120 million in 1200, to half that level, 125 years later.

Although China began

to recover, under the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368-1911), growth fell short of the requirements for sound economic development

that we have described. Problems developed in the Chinese economy, as China failed to maintain a commitment to continual scientific

and technological progress.

Although China grew, in area and population, the percentage of the population living

in urban centers actually decreased. Following the Mongol invasion, no city again reached 1 million until 1850. China's population,

which was about 60 million in 1368, increased to some 200 million by 1600, reaching around 430 million in 1850. However, in

1820, the level of urbanization had declined to 7%, a dramatic decrease from the 20% level of 600 years earlier.

That

China did not maintain and further increase the level of urbanization during this period, is indicative of its failure to

continue scientific and technological progress. The increased population remained in the countryside, where it continued to

use the same technology. Tragically, rather than creating new industries to utilize the increased population, more labor-intensive

techniques were introduced in agriculture, for example, a plow designed to be pulled by humans.

The shift towards

more labor-intensive practices, decreased the output per person, and lowered the potential relative population-density. None

of the conditions, that we have described as necessary for successful economic development were met. The population's living

standard declined. Consequently, the implements used by many of the farmers, at the beginning of the 20th Century, were more

primitive than those described in a 1313 book by Wang Chen.

Also, the destructive effect on China of British opium

trafficking during the 19th Century cannot be underestimated. The amount of money looted out of China was so massive that

it caused a severe disruption of the economy and society. By 1900, a great part of government revenues went to pay debts forced

on the Chinese as war reparations, for attempting to defend themselves from the British opium traffickers. Even worse, it

was precisely the intelligentsia, who would have mastered and introduced the new technologies of the West, who were destroyed.

By 1880, there were an estimated 30-40 million opium addicts, or possibly, even more.

China Moves Into the Twenty-first Century

Chinese President Jiang Zemin

The true heirs of the Renaissance, such as Leibniz, sought to form an alliance between Europe and China, combining the best

of both cultures. Leibniz proposed that, ``as the most cultivated and distant peoples [Europe and China] stretch out their

arms to each other, those in between may gradually be brought to a better way of life.''

During the last 25 years,

China has undergone a remarkable period of development. Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping took personal responsibility for relaunching

the nation's commitment to science and technology, in the aftermath of the disastrous Cultural Revolution. Deng grasped its

importance for successful development: ``We often say that man is the most active productive force. `Man' here refers to people

who possess a certain amount of scientific knowledge, experience in production and skill in the use of tools to create material

wealth. There were vast differences between the instruments of production man used, his mastery of scientific knowledge, and

his production experience and skills in the Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages and in the 17th, 18th, and 19th Centuries. Today,

the rapid progress of science and technology is speeding up the introduction of new production equipment and new technological

processes.'' Deng stated that fostering in the Chinese people, a conscious commitment to raising their level of scientific

and general knowledge, would allow the them to achieve a higher level of productivity than nations that did not develop this

conscious commitment in their people.

China's President Jiang Zemin has also located the development of the creative

powers of the human mind as the central task for China. He stated, ``The progress of human civilization has more and more

convincingly proved that science and technology constitute a primary productive force and an important driving force for economic

development and social progress.... Human wisdom is inexhaustible. Science and technology are a shining beacon of this wisdom.''

The very survival of the United States depends on an agreement for a New Bretton Woods monetary system, which will

necessarily include China. Americans would do well to study the 5,000-year history of China, in order to gain a sense of history,

needed to approach the tasks that both nations face in overcoming the crisis that is now engulfing the world.

|